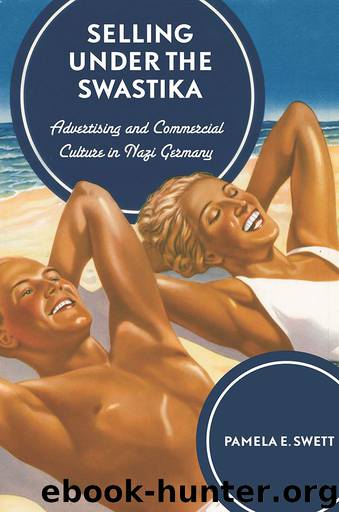

Selling under the Swastika: Advertising and Commercial Culture in Nazi Germany by Swett Pamela

Author:Swett, Pamela [Swett, Pamela]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2013-12-18T00:00:00+00:00

PART III

Preparing for Victory and Surviving Defeat

CHAPTER FIVE

Advertising in the First Half of the War

Those who advertise announce they are alive.1

By late August 1939, companies selling consumer items found themselves paralyzed by the uncertain political situation. When the “hoped for release of tension” did not materialize, Henkel assured its traveling staff that headquarters understood that “normal visits to customers and the work of our ad ladies are no longer possible in any usual way.” Suggestions were made for ways to keep busy: “[P]erhaps make an inventory of your ad materials, bring your [customer] cards in order; there may be one or two customers to visit in order to reassure.” The Werbedamen were to be released from their duties until further notice, “since demonstrations of washing methods will now only be poorly attended.” All film equipment was to be stored in fire-proofed garages. Soap rationing had arrived, though Henkel complained that the press releases on the matter had not been clear that Persil fell among “soap powder” rather than “cleansers.” Another way to keep busy, therefore, was for sales staff to clarify the situation with their wholesalers.2 Of course these plans were all somewhat moot—this was not a situation in which companies enjoyed the freedom to set their own agendas. Twelve days later, Henkel announced the introduction of the “unity cleaning powder, which meant in other words: For the time being, there is no more Persil.”3

The question, then, for this chapter is what the war economy meant for the buying and selling of consumer goods. The quotations above seem to provide an obvious answer. Brand-name consumer products and the advertising to promote them were to disappear from the marketplace. For the Werberat too it appears that its usefulness was at an end and that earlier calls for its dissolution would no longer be ignored. At best, Ad Council staff members could hope to be integrated directly into the Propaganda Ministry in service of the war. The scholarship on consumption in Germany bears out these conclusions, taking a sharp turn in 1939. Some scholars simply end their analyses at the war’s onset, while others indicate through their emphases on shortages and ersatz products that the war years signify most simply the end to individual consumption and its replacement with a form of war socialism that failed to meet the needs and desires of consumers.4 One exception is Götz Aly, who has maintained that allegiance to the regime was secured through the dissemination of goods stolen from Jews and the occupied territories.5 But his arguments have not convinced everyone, and his focus on the distribution of goods merely as a means of generating political support says little about how the distribution of war loot fit in with wider patterns of consumer expectations and long-term economic thinking.

This chapter will challenge those who discount the significance of buying and selling during the war years, and will also confront Aly’s view by emphasizing the active role taken by the private business sector to shore up the home front.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Brazilian Economy since the Great Financial Crisis of 20072008 by Philip Arestis Carolina Troncoso Baltar & Daniela Magalhães Prates(133694)

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(108810)

The Art of Coaching by Elena Aguilar(53176)

Flexible Working by Dale Gemma;(23284)

How to Stop Living Paycheck to Paycheck by Avery Breyer(19713)

The Acquirer's Multiple: How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market by Tobias Carlisle(12308)

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Kahneman Daniel(12248)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12013)

The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli(10443)

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9121)

The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy(8941)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8363)

Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results by James Clear(8319)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8040)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7809)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(7753)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7689)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7466)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(7183)